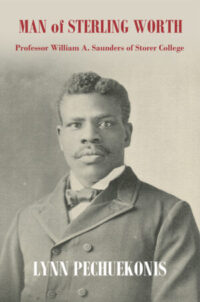

UPDATE OCTOBER 2022: This story has been expanded and turned into a beautiful new book. You can order your copy from the Harpers Ferry Park Association Bookshop.

UPDATE OCTOBER 2022: This story has been expanded and turned into a beautiful new book. You can order your copy from the Harpers Ferry Park Association Bookshop.

“… So now, students, it is necessary to make use of every moment that comes to us; for while the present is great and grand the future to which we are looking will be more great and grand if we have the determination to make it so.”

Knowing something of the times in which he wrote, we are amazed and inspired by the optimism of the young Black man who authored these words as he completed his education at Storer College in 1895. He was William Allen Saunders, age 25 at the time, who later became the original owner of our home. We are excited to share with you what we have learned about him and his wife.

Saunders was born on January 15, 1870, the son of Hezekiah and Louisa (Thompson) Saunders, who were almost certainly recently freed slaves. They lived near the historic town of Louisa, Virginia, along today’s U.S. Route 33. Judging from what we have learned of William’s life, they must have instilled in him a thirst for education along with an incredible capacity for hope.

Saunders arrived in Harpers Ferry to finish his secondary education at Storer in the early 1890s. Shaped by his time in this oasis from the harsh world of Jim Crow laws, he was brimming with confidence about his prospects in spring 1895. As a co-editor of the Storer Record, his writing clearly reflected the character and leadership promoted by the school. In his farewell editorial, he encouraged his fellow students, especially those who were worried that their “great hope of being rewarded” for their academic labors might not be realized due to the “present condition of affairs in the country”:

…Let us show ourselves men, for the destiny of the country lies in the hands of the young men of our generation and if we wish to see the country hold its place in history and continue to raise the stars and stripes over the dome of the capitol we must enter the arena with the interest of the government at heart. Unless this is done we shall surely fail to have our names associated in history with those of great men. Finally, students, with a pure and earnest purpose of heart, let us keep our eyes steadfastly fixed upon the future welfare of the race and the prosperity of the country.

With an earnest expectation of influencing the destiny of his country, Saunders went on to earn a bachelor’s degree from Bates College in 1899. The following information comes from the “History of the American Negro” (West Virginia Edition, by A. B. Caldwell, 1923), which is archived by the West Virginia Division of Culture and History:

When ready for college, [Saunders] went North and matriculated at Bates College. … Speaking of his struggles there, he said, “As I had but $25.00 when I reached Bates College, it was necessary for me to get all the work I could. So I would do house cleaning or any little thing that would bring me some little money. In the summer, I worked by the day, getting from a dollar to a dollar and a half per day, and in this way was nearly able to meet my expenses.”

Prepared as an educator, Saunders taught in several schools (mostly in West Virginia), until in 1907 he returned to Storer College as a member of the faculty. Over the course of his four-decade tenure at Storer he taught courses in Natural Science, Mathematics, Latin and Religious Studies courses.

Saunders also served for many years as treasurer of the Alumni Association and encouraged alumni participation and fundraising through the Storer Record. In one amusing entry, the newsletter included this one-liner: “Prof. Saunders for a few days was a victim of gripe, lumbago, or both.”

While Saunders was teaching at Bluefield Institue he met and fell in love with Inez Marie Johnson. (She was born in 1888 to Jacob and Mattie Johnson, of Institute, W. Va.). They were reunited when Saunders joined the Storer faculty. Inez was in her second year of the teacher preparation program. In a 1908 issue of the Storer Record Inez published a thoughtful article on the educational value of magazines, which ended this way:

…All classes of mankind want a more substantial degree of knowledge, a degree of knowledge that is not selfish but helpful; that does not breed hostility but kindness; does not degrade but elevates. … Knowledge of this kind brings happiness and comfort. Happiness and comfort help us to see more clearly the needs of others, and when we have been educated as to be able to see these needs, and we are in position to administer to them we then are doing God’s service, for ‘We were made to radiate the perfumes of good cheer and happiness, as much as a rose was made to radiate its sweetness to every passer-by.’

We don’t know what stood in the way of any earlier marrage, but Inez graduated and left for her first teaching job in Cooper, W.Va. She wrote back to the Record, “I have a very good school building here. It is new and situated in a very nice place.” The entry continues: “With fifty children 6 to 18 years of age to teach she is kept busy enough.” (Unfortunately, we have not yet located a photograph of Inez.)

She eventually returned to Harpers Ferry, and the couple married on September 10, 1914. Inez was 26 and William was 44.

Two years later William purchased a double lot at 900 Fillmore Street, just down the hill from Storer toward Union Street. It took a decade before their beautiful three-and-a-half-story stone foursquare, was completed. Its 1927 assessed value according to the Jefferson County tax records was $2,500.

We are curious about how William could have afforded such a large and beautiful house. A letter from President McDonald in 1923 lists William’s salary as “$910, House,” with no other detail. We have seen a map showing that the couple initially had a house on the Storer grounds. The College was known to have helped some faculty members and alumni with home ownership, and the Saunderses may have been beneficiaries of their assistance.

Nevertheless, William and Inez were able to extend the Storer bubble a couple of blocks on down the street and lived out their lives here within the home’s 18-inch-thick solid rock walls embellished with Craftsman-style woodwork. (The name Rockhaven was invented by us; as far as we know they never named the house and probably would never have thought of doing so.)

Inez continued teaching in Harpers Ferry schools for Black children. Her 25-year-long career ended, sadly, when in 1937 she took ill. After six months of decline, she died at age 49. Her obituary says that she “was well known, and very highly esteemed by both white and colored residents of the twin towns [Harpers Ferry/Bolivar]. She was a woman of sterling Christian character.”

William was her only survivor, and he never remarried. He must have missed her very much.

William continued teaching at Storer, and his name appears on many special event programs as a speaker giving a talk or invocation. He retired in the early 1940s, although, according to Storer academic catalogs, he was still teaching one or more courses until 1951.

The Spirit of Jefferson newspaper reported on the Storer College 80th anniversary celebration on March 5, 1947, identifying Saunders as Professor Emeritus:

“Professor Saunders gave stirring remarks in memory of the founders of the College and placed a wreath below the picture of Dr. N. C. Brackett, first President of the College.”

In a 2017 conversation with alumnus Elbert Norton (Class of 1955), he recalled Professor Saunders, who would have been in his 80s at the time Norton was a student. He said that Saunders voluntarily kept his mailbox at the college, which forced him to walk up the hill every day to fetch his mail. One time Norton was asked to deliver the mail to the Saunders’ home. He remembers seeing books everywhere in sight and said there was even a podium in the parlor so Saunders could read standing up.*

Saunders’ favorite reading, according to Caldwell’s biography, consisted of History, Science and Literature. “He knows of no short cuts to progress for the race or for the individual,” the article continues. He told his interviewer, “The best interests of the race may be promoted by teaching the use of every opportunity for betterment and above all the saving and wise investment of money.”

Saunders owned his Fillmore Street home until deeding it to local educator Carrie Dennis in 1962, well past the 1955 closure of the college. A beautiful headstone in Cedar Hill Cemetery has the Saunders name on it in large letters. Inez’s birth and death dates are engraved on it, but only William’s birth date. We finally discovered that he William had moved in with his grandniece, Elsie Saunders Dodson, in Laurel, MD. He died there in 1963 at age 93.

We continue looking for more Saunders history whenever we get a lead. We know enough, though, to be very proud to be living in a home that once belonged to a faithful couple, whose lifelong dedication to education overcame society’s many obstacles and surely touched countless lives for good.

*In-person conversation, October 7, 2017, Storer College 150th anniversary celebration.

This post was updated with additional information on August 18, 2021.

Oh I am almost certain that he had children, just not from his marriage. I will certainly provide an update after I get confirmation.

Phillip, we’re so curious to see your information!